It is helpful to take a historical view to contextualise the global COVID19 pandemic. Without this history, our public imagination cannot place this crisis within our sense of how the world was, is, or could be. The 1918-20 pandemic (with its 50 million deaths) is well before ‘living memory’. When we do try to remember this ‘Spanish Flu’ of one century ago, we use that very phrase: a racist name which by using the word ‘flu’ also minimises the deadly nature of that pandemic.

So let’s be honest: our public imagination is centred in contemporary times. Our public memory, or popular sense of history, goes back into the 20th century.

Generations alive today have witnessed the 1981-current HIV/AIDS epidemic (35 million deaths); the 2009 Swine Flu (200,000 deaths); and the 2014 Ebola epidemic (11,000 deaths). Each infectious disease has been transnational in spread and devastating in effects.

Our focus blurs when looking prior to 1900. In addition, histories of infectious disease have to a certain extent been the concern of specialists within the medical community and the academy.

COVID19 as modern ‘plague’

Earlier in 2020 Australian writer Arnold Zable began referring to the COVID19 pandemic as ‘plague’ in his extraordinary ongoing Facebook series ‘What We Do In the Time of the Plague’. There, Zable shared observations from life in Melbourne in 2020 and now 2021. The second time I heard the word used was in a piece on Albert Camus’ 1947 novel The Plague.

New York Times writer Elizabeth Bruenig’s informative podcast on The Bubonic Plague, is grounded in primary source accounts and her own reflections:

The fact is that the millions of people who died in “the great mortality” were human beings who were sick … and they were suffering from something they didn’t understand, and they were trying to overcome it.

Elizabeth Bruenig on the Bubonic Plague

Bruenig’s podcast affirms what’s right before our eyes: that the COVID19 pandemic is the latest in a long history of plagues and pandemics recurring throughout the centuries.

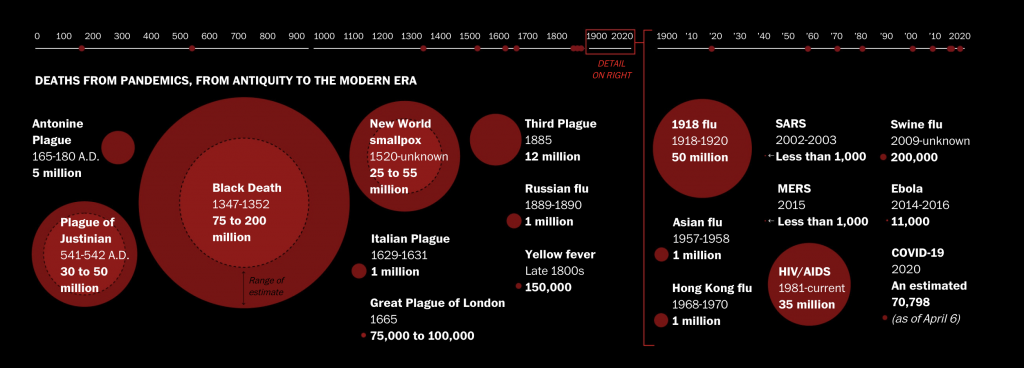

Thanks to the graphic below, here are four deadly pandemics which occurred prior to 1900:

- the Plague of Justinian (541-542 CE: 30 to 50 million deaths);

- the Bubonic Plague or “Black Death” (1347-1352 CE: 75 to 200 million deaths);

- New World smallpox (1520 CE: 25 to 55million deaths);

- “Third Plague” (1885: 12 million deaths).

The current (3 January, 2021) Johns Hopkins figure for global deaths due to COVID19 stands at 1,844,518 with over 85 million confirmed cases.

A history of plagues and pandemics

It is important for us to become more conscious of the dynamic history of plagues and pandemics, and the human stories of those who lived through them. Reading this history helps us achieve a more clear-eyed view on what kind of event we are now living through. Reflecting on this history will prepare us to find the strength, courage and resilience to carry on without being in denial of how hard things are.

What follows are accounts of three plagues, one for each of the last three millennia. I then conclude with an observation about how the current pandemic has centred us on what matters.

The Plague of Athens (432 BCE)

“In 430 BC, a plague struck the city of Athens, which was then under siege by Sparta during the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC). In the next 3 years, most of the population was infected, and perhaps as many as 75,000 to 100,000 people, 25% of the city’s population, died.”

Robert J Littman, 2009, The plague of Athens: epidemiology and paleopathology

About this Plague of Athens, the so-called ‘father of history’ Thucydides wrote (as quoted on the Plague Lit: Past Wisdom for the Present Crisis website):

Neither were the physicians at first of any service, ignorant as they were of the proper way to treat it, but they died themselves the most thickly, as they visited the sick most often …

People in good health were all of a sudden attacked by violent fevers in the head, and redness and inflammation in the eyes, the inward parts, such as the throat or tongue, becoming bloody and emitting an unnatural and fetid breath. These symptoms were followed by sneezing and hoarseness, after which the pain soon reached the chest, and produced a hard cough …

By far the most terrible feature in the malady was the dejection which ensued when any one felt himself sickening, for the despair into which they instantly fell took away their power of resistance …

It was with those who had recovered from the disease that the sick and the dying found most compassion. These knew what it was from experience, and had now no fear for themselves; for the same man was never attacked twice-never at least fatally.

Thucydides on the Plague of Athens

With “death raging within the city and devastation without….Such was the history of the plague.”

The Yellow Plague (664 CE)

In 731 CE, the English monk-historian Bede The Venerable recalled ‘The Yellow Plague’ of 664. Medical historians now describe this disease as ‘Smallpox’. It was understood to be spread by air and close contact, with the Plague Lit site reporting that “one Welsh source described it as a veil of rain sweeping through the countryside”. Sounds familiar!

Bede wrote:

In the same year of our Lord 664, there happened an eclipse of the sun, on the…[first] day of May…In the same year, a sudden pestilence depopulated first the southern parts of Britain, and afterwards attacking the province of the Northumbrians, ravaged the country far and near, and destroyed a great multitude of men [people]…

The Venerable Bede on The Yellow Plague

The Bubonic Plague (c. 1347-1352)

In her podcast, Elizabeth Bruenig quotes from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron written in 1350. In this work, the Italian poet and scholar reports direct from the Bubonic Plague, when in 1348 “the mortal pestilence then arrived in the excellent city of Florence … Sick persons were forbidden entrance, and many laws were passed for the safeguarding of health… almost at the beginning of the Spring of that year, the plague horribly began to reveal, in astounding fashion, its painful effects.”

Deadly swellings known commonly as ‘plague-boils’ would appear on infected persons. “Neither the advice of a doctor nor the power of any medicine appeared to help and to do any good … Not only did very few recover, but almost everyone died within the third day from the appearance of these symptoms, some sooner.” The pestilence spread “as fire does” with “the clothing or other things touched or used by the sick” bringing the disease.

Boccaccio’s account describes people prioritising their own health over all else: “Almost all were inclined … to shun and to flee the sick and their belongings. By so behaving, each believed that he would gain safety for himself … Many men and women abandoned their own city, their houses and homes, their relatives and belongings in search of their own country places or those of others” because they felt safer outside the major cities.

In an extraordinary passage, Boccaccio explains the effect of the plague on human relations:

We have said enough of these facts: that one townsman shuns another; that almost no one cares for his neighbour; that relatives rarely or never exchange visits, and never do they get too close. The calamity had instilled such terror in the hearts of men and women that brother abandoned brother, uncle nephew, brother sister, and often wives left their husbands. Even more extraordinary, unbelievable even, fathers and mothers shunned their children, neither visiting them nor helping them, as though they were not their very own.

Giovanni Boccaccio on the Bubonic Plague in Florence

Trenches were dug as burial grounds, and “in the scattered villages … and across the fields, the wretched and impoverished peasants and their families died without any medical aid or help from servants.”

Elizabeth Bruenig also quotes from Agnolo di Tura’s The Plague in Siena: An Italian Chronicle. Di Tura reported that “The mortality began in Siena in May (1348). It was a cruel and horrible thing… in many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead. And they died by the hundreds both day and night … I buried my five children with my own hands.”

Bruenig reflects that in these times “a certain kind of nihilism began to spread in some quarters, with a grim ‘seize the day’ mentality gaining purchase. Eat, drink, be merry … tomorrow you may die.”

“We’re going to make it somehow”

Perhaps we avoid the histories of plagues and pandemics because we sense the suffering, trauma, loss, grief and lamentation involved. Great creativity emerges in times of plague too, however, helping us to find cause for reliable hope. For example, the Plague Lit site observes that Martin Rinkart may have composed the hymn Now Thank We All Our God during the plague of 1636:

Now thank we all our God

with heart and hands and voices,

who wondrous things has done,

in whom his world rejoices …

The anonymous scribe comments “seen in light of the plague, the hymn is less a triumphant proclamation of gratitude, and more a poignant statement of simple faith in a time of crisis.”

Every pandemic or plague brings death to many and upheaval to all. In Elizabeth Bruenig’s words, people left behind at the end of the Bubonic Plague “looked at the wreckage of society around them, and said, we’re going to make it somehow.”

In a similar way, the COVID19 pandemic is connecting us with what matters. We can more readily perceive life as gift because we are that much more conscious of mortality. And we can remember the wisdom of all ages: that light shines brightest in time of darkness.

Leave a Comment