The individual who killed 51 people at prayer in Christchurch Mosques on Friday 15 March 2019 is Australian. As Shakira Hussein wrote in The Saturday Paper on 12 December last year:

For me, and for many other Muslims living in Australia, the Christchurch attack has always felt like an Australian crime that happened to take place in Aotearoa…

There needs to be a moment of reckoning that the man behind the Christchurch massacre is an Australian. He was born here, and it was in this country that his hatred and racism developed at a young age.

Christchurch massacre: an Australian crime, The Saturday Paper, 12 December 2020

Hussein was reflecting on the crime soon after the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Terrorist Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019 delivered a report to the New Zealand Governor General entitled Ko tō tātou kāinga tēnei: This is our home. In their end note the commissioners write “Out of the terrible events of the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack has come the responsibility to reflect and learn.” We in Australia must take time to reflect on the report’s findings, which deserve solemn and sober reading.

The terrorist was formed by life in Australia

Throughout their report, the commissioners describe the Australian terrorist as “the individual”. In a section entitled Part 4: The Terrorist, they outline the individual’s life trajectory “from childhood in Australia through to the terrorist attack in New Zealand.” The Report Summary observes:

The individual is a white Australian male who was 28 years old in March 2019. He displayed racist behaviour from a young age. His life experiences appear to have fuelled resentment and he became radicalised, forming extreme right-wing views about people he considered a threat. Eventually, he mobilised to violence.

The individual arrived in New Zealand on 17 August 2017. As an Australian, he was entitled to live in New Zealand. Within a few days of arrival, he moved to Dunedin and from this time, his life was largely devoted to planning and preparing for the terrorist attack.

The report tells a story of relevant aspects of the individual’s life and formation in Australia.

The individual … was twice dealt with by one of his high school teachers, who was also the Anti-Racism Contact Officer, in respect of anti-Semitism. This teacher described the individual as disengaged in class to the point of quiet arrogance, but also well-read and knowledgeable, particularly on certain topics such as the Second World War …

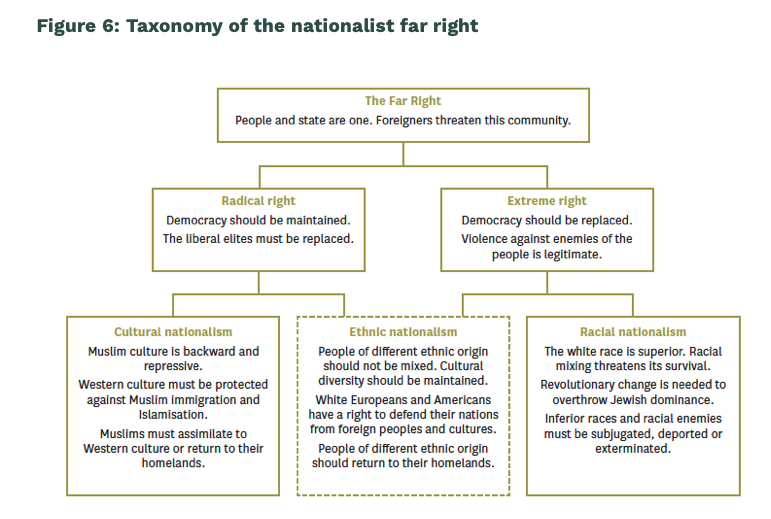

The individual told us that he began to think politically when he was about 12 and that his primary concerns have been about immigration, particularly by Muslim migrants into Western countries. In his manifesto he said that he had no complaints with ethnic people, if they remained in their places of birth. Those on the far right, particularly ethno-nationalists (as described in Part 2, chapter 5), sometimes assert similar views while disingenuously denying being racist. Aspects of the individual’s life are consistent with his description of his views.

Part 4 The Terrorist: Chapter 2 The individual’s upbringing in Australia

From far-right radicalisation to violence

The commissioners observe “the individual’s political thinking was far right in nature and showed many of the signs of ethno-nationalism”. Describing the process whereby a person moves from ‘radicalisation to violence’, they write:

Most people with extreme right-wing views do not act on these views through violence. The process through which people develop commitment to a particular extremist ideology is called radicalisation. The process through which an individual comes to see violence as a feasible tool to address their grievances is called radicalisation to violence ...

Radicalisation is almost universally acknowledged as a group phenomenon in which social relations and networks play a key role in preparing people to commit extremist violence. A person may come into contact with extremists in a multitude of ways, such as through existing networks of friends and family, public outreach by those involved in these groups or, increasingly, online engagement. When someone with generalised grievances comes into contact with individuals or groups who are able to provide a wider framework through which they can understand their grievances, extremist worldviews can be reinforced …

Participation in a group enables a range of processes that may facilitate the use of violence, including a solidifying of dehumanising thinking, an increased perception of crisis and belief in the use of violence as a legitimate tool.

Part 2 Context Chapter 5.4 Radicalisation to violence

On 30 August 2020, a spokesperson for Australia’s domestic spy agency ASIO said “extreme right wing groups and individuals represent a serious, increasing and evolving threat to security” and the Christchurch attack was a “stark example of this”:

Unfortunately, extreme right wing groups are more organised, sophisticated and security conscious than before. These groups are becoming increasingly ideological; more aware of and committed to specific dogmas, philosophies and views, many of which support or glorify violence. They draw from a diverse variety of ideas and they are attracting a younger membership who display few overt signs of their extremist ideology.

Far-right radicalisation via the internet

In September 2020, ASIO Deputy Director-General Heather Cook “confirmed right-wing violent extremism now accounted for between 30 and 40 per cent of its current caseload in counter-terrorism work. This compared to between 10 and 15 per cent prior to 2016.” A report in the Sydney Morning Herald quoted Cook ‘saying the way in which extreme right-wing extremists were using the internet to recruit the “young and vulnerable” was similar to the methods deployed by Islamic State at its peak, adding the strategy was being used “to good effect”.’

Now one month after the violent insurrection at the United States Capitol, governments and media platforms are renewing their conversations about curtailing far-right extremism on the internet. The social media app “Parler” which hosted extremist views and conversations has been removed from Google, Apple and Amazon platforms.

In part 2 chapter 5.3, the commissioners observe the ways the internet has incubated far-right thinking:

One of the most notable changes in the right-wing extremist movement has been its movement from the streets to the internet. In previous decades, the extreme right-wing mostly organised on the streets in gangs or protest movements. Today, extremism has substantially, although not completely, moved from physical meetings and street activism to the internet and social media.

Part 2 Context Chapter 5.3 The nationalist far right, the radical right and the extreme right-wing

Social cohesion and safety for all

Violent far-right extremism is a volatile phenomenon which requires a whole-of-community response. The Royal Commission meditated at length on social cohesion as a factor which may protect against similar terrorist attacks in the future.

For the commissioners, social cohesion is “where people feel part of society, family and personal relationships are strong, differences among people are respected and people feel safe and supported by others.”

The commissioners found that social cohesion actively discourages far-right violence:

Social cohesion can contribute to preventing or countering extremism. This is because cohesive and resilient communities are better placed to resist and counter the risk of radicalisation and mobilisation to violent extremism and terrorism. Tolerant, and ideally inclusive, societies are more able to address and prevent the polarisation and disenfranchisement that can contribute to a rise in extremism.

Part 9 Social cohesion and embracing diversity Chapter 1 Introduction

The commissioners invite the New Zealand public to conversation about social cohesion as a way to build a more robust democratic society where residents readily respect each and every community. Such a society guards against extremist violence.

These reflections have implications for all Australian governments, communities and residents. Australia certainly has a way to go before we may more universally hold together peacefully the values of diversity and democracy.

Here are some of the commission’s recommendations which should be read closely in Australia.

Australia-relevant report recommendations

Recommendation 4

We recommend that the Government:

Develop and implement a public facing strategy that addresses extremism and preventing, detecting and responding to current and emerging threats of violent extremism and terrorism …

Recommendation 15

We recommend that the Government:

Create opportunities to improve public understanding of extremism and preventing, detecting and responding to current and emerging threats of violent extremism and terrorism in New Zealand …

Recommendation 36

We recommend that the Government:

Invest in opportunities for young New Zealanders to learn about their role, rights and responsibilities and on the value of ethnic and religious diversity, inclusivity, conflict resolution, civic literacy and self-regulation.

Recommendation 40

We recommend that the Government:

Repeal section 131 of the Human Rights Act 1993 and insert a provision in the Crimes Act 1961 for an offence of inciting racial or religious disharmony, based on an intent to stir up, maintain or normalise hatred, through threatening, abusive or insulting communication with protected characteristics that include religious affiliation.

In the explainer prefiguring recommendation 40 from ‘Part 9 Chapter 4 Hate crime and hate speech’ a new offence was drafted: Every person commits an offence and is liable on conviction to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years who:

- with intent to stir up, maintain or normalise hatred against any group of persons in New Zealand on the ground of the colour, race, or ethnic or national origins or religion of that group of persons; and

- says or otherwise publishes or communicates any words or material that explicitly or implicitly calls for violence against or is otherwise, threatening, abusive, or insulting to such group of persons.

Conclusion

The findings and recommendations of the New Zealand Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Terrorist Attack on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019 should give us pause. I encourage Australians reading this post to read the report. As the neighbouring nation whose communities shaped this terrorist, we must be willing to read, learn, and be changed by what we learn.

We who are seek to build peace do well to reflect carefully on the causes of violence, and consider what happened in this case. After reading the parts of the report I was drawn to, I am engaged in the following questions:

- Are our communities capable of stopping persons who are radicalising before they turn to violence?

- What strategies do we have to redirect such persons and their energies?

- Do our cities, schools, workplaces, sporting clubs and communities truly value diversity and difference?

- What will we do to build a more robust democracy which is confidently pluralist in nature?

We can all contribute to building communities which embrace difference, nourish respect, encourage mutuality, and build solidarity among all. Our responsibility to the common good demands no less.

Leave a Comment