‘Tell me about a complicated man.’ So begins Emily Wilson’s luminous translation of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey.

As I quickened my way into reading this poem, I felt consumed by and drawn into its ocean-world of light and dark. Odysseus is a bold adventurer, a passionate and courageous warrior of the seas. Now far from home, he yearns to return and so to be with his loved ones. Many obstacles come his way. The route is curcuitous and takes him to the edge of death. His every misfortune calls him to lean on the hospitality of strangers and to seek the favour of the intervening gods and goddesses.

Odysseus is a ‘big’ and complex character. He will succumb to his own weakness, even when forewarned. He can say outrageous things. But within a context of his bravado and ‘heroism’, the world of the text seems to welcome (and then challenge) his ego. The gods care deeply about his journey, wondering what to do with him. Their various interventions often come disguised (Athena’s especially). His ship’s crew are skilled on the high seas and independently-minded on land. I often wanted to hear more from them.

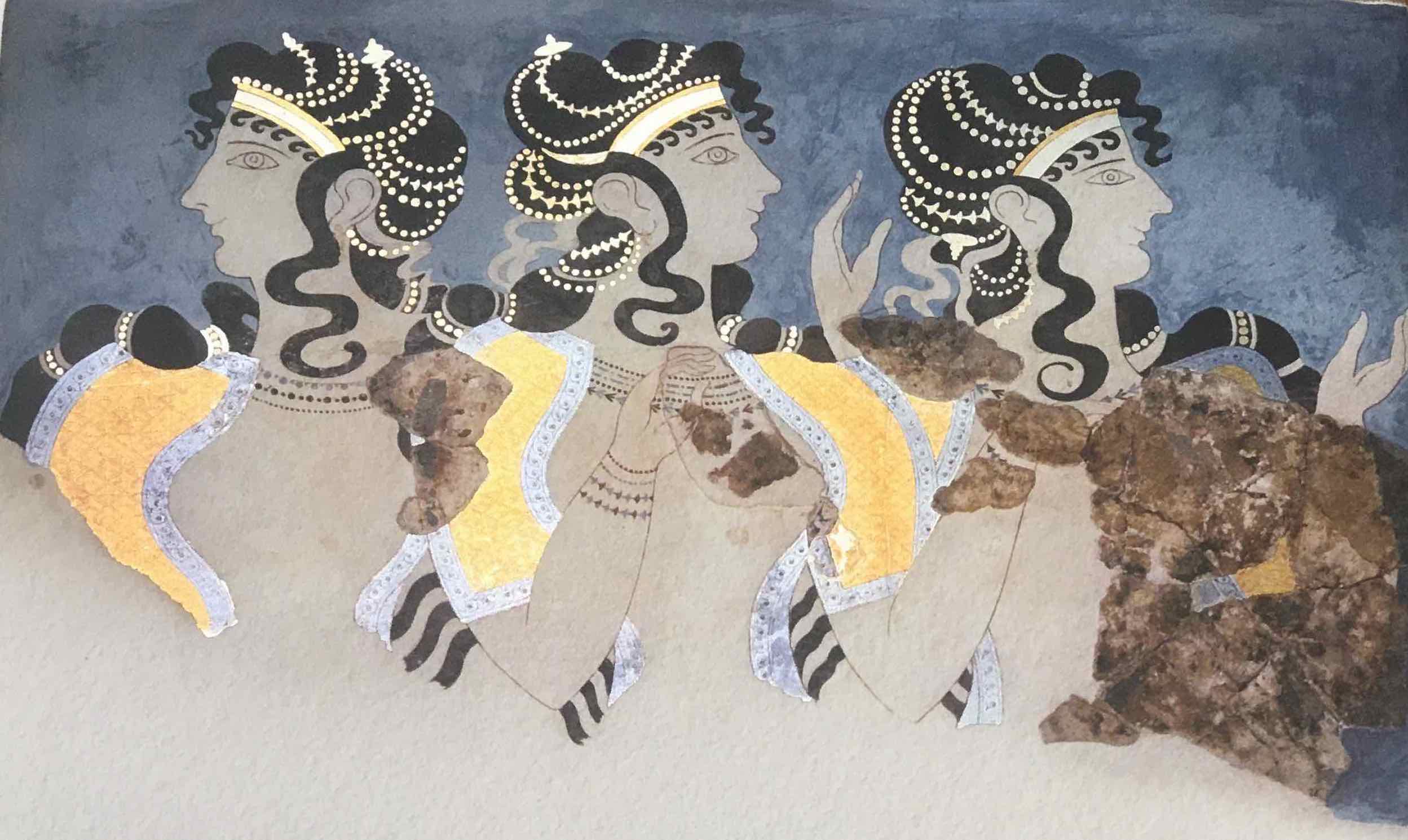

Much had been said in reviews about Wilson’s skilful and sensitive rendering of the scene when Odysseus hears ‘the otherworldly Sirens’ singing to him from their island. Having anticipated this part of the text so much, when I read these lines I gasped in appreciation. Much of the text was like this, moving me to pause to savour and lather in the word pictures crafted by Wilson’s translation.

A prompt for self-reflection

Significantly, Odysseus’ journey took me deep into reflecting on my own. The poem’s language, image and metaphor speak to some of my experience. I too have crossed unknown seas to strange shores. There have been times I have felt far from home and longingly sought return. Looking back, I recognise that I have experienced the restorative power of providential journeying, cast forward by a grace I can only attribute to divinity. I have also experienced the upheaval brought about by spirits of unease and distress here attributed to lesser gods.

The experience of reading this poem gave me a generous feast for the senses, a magnificent meal for the imagination. I often paused to appreciate the beauty of the translation which sings like a top choir hitting all the notes of their renaissance polyphony. This is a gorgeous, big-hearted, uplifting, and transformative experience of Homer’s epic. I felt invited to enter a larger world.

Thanks for sharing, James.

I’m reminded of Keats:

On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer

By John Keats

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Over the decades I’ve read first Rieu’s Penguin Classics translations, and then Lattimore a couple of times, and bits of Fitzgerald. I’ve only dipped into Wilson’s translation, but even so I’ve found it illuminating and engaging. Having read your reflections, I’ll move it up my ‘to read’ list.

Best wishes, Denis Fitzgerald

Thanks very much for your comment Denis and for reading my take on the text. I appreciate greatly your sharing the Keats poem which captures the feeling. In particular, it holds my own experience of having all the senses open to receive the world of Wilson’s translation. I hope you enjoy returning to this translation when you get the chance! And my best wishes in these challenging times.