A beautiful documentary film That Pärt Feeling: The Universe of Arvo Pärt (2019, Paul Hegeman – Vimeo) brings together musicians, conductors and collaborators to celebrate Arvo Pärt’s musical life. Viewers are taken behind the scenes of several rehearsals and performances, and given insights from people whose work has been entwined with Pärt’s. The Estonian composer is the world’s most-performed classical music composer alive.

Each musician commenting on the impact of Pärt’s music speaks with awe, enthusiasm and even love. Estonian conductor Tõnu Kaljuste describes the journey Pärt has been on across decades of creative work together. This is seen best in the changes that occur across the four symphonies. For Kaljuste, Pärt’s music has “distance, which at the same time touches you”.

Classically trained electronic musician Kara-Lis Coverdale credits the composer with returning her to “fundamentals in music”. She points to Pärt’s use of triad chords: they “somehow sound so full, you don’t really need anything else”. Coverdale describes the angles and form in the music as architectural and almost mathematical. Whether listening or playing, she sees clear lines, not images, nor a romantic vision.

Alain Gomis created a film, Félicité, where Orchestre Kimbanguiste de Kinshasa perfomed “Arvo Pärt digested by the Congo”. They play Antiphones which “represents a kind of beauty that can exist in your heart.” Gomis observes that “[Pärt’s] music influences the way you look… it takes you to a place you don’t know, but which you recognise as a human being.” Indeed, Pärt’s works affirm the significance of our daily experiences.

Raoul Boesten of the Chamber Choir Kwintessens comments that Pärt’s music “puts you at ease, it relaxes you, it brings you closer to yourself. It’s confrontational, but at the same time comforting.” Boesten retells one of Pärt’s stories of having attended a concert where a dog was present. The music was played beautifully, and at each climax, the dog would howl. “Arvo Pärt loved that the dog was so ecstatic.”

Pärt invites musicians and listeners alike to take a risk and allow his music to impact us. One collaborator comments that playing Pärt’s compositions involves “walking on thin ice – very beautiful but always with some danger.” A story is told of a person in Wales who approached the musicians to describe an emotional catharsis experienced during a concert, where now they want to do life differently. So it is “you have to take his music seriously. He intends something great with his music.”

The composer appears in the film to give guidance to the Cello Octet Amsterdam as they play his music. Pärt moves his body in step with the musical phrases, backwards and forwards, mouth open, and clicking to draw the music to a pause. He affirms that such music, as a communal enterprise, is not about virtuosic individuals, but a union of voices.

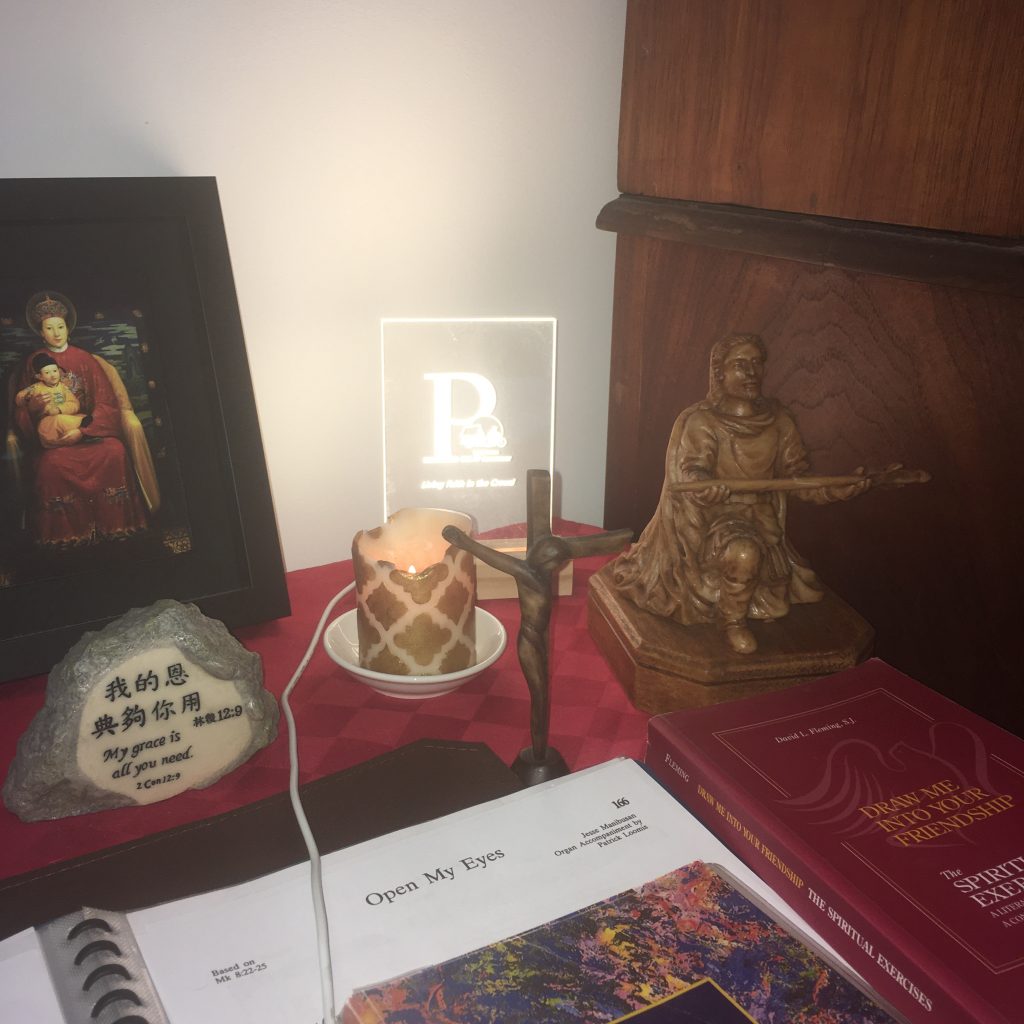

The spiritual commitment of Pärt to Christian faith fills his music with scriptural inspiration and a sense of mystery at the centre of things. Take Fratres, for instance, which is “about fraternity and unity” while not shying away from naming “the rupture between people”. The music becomes a prayer for those listening. “What he has to say is so extraordinary – his music takes you on a spiritual journey.”

The attentiveness and care Pärt offers to the cello ensemble inspires them to unite in creating something beautiful. The last lines in the film are Pärt’s: “One always has to dust off the old sounds. It is also important for me when I listen or when I work together with others, to have a creative access. We have to come together and then give new life to work. That’s how it is.”